The Johnson & Johnson talcum powder multidistrict litigation (MDL) is currently the second largest MDL in the nation, with over 35,000 lawsuits filed.

On August 18, the plaintiff in a Philadelphia trial claimed J&J was aware that its iconic talc-based baby powder was associated with cancer risk but withheld that information from consumers and regulators for decades in order to protect its brand image, Law360.com reported.

The most recent talc trial is Ellen Kleiner et al. v. Johnson & Johnson et al., which is being held before the Court of Common Pleas of Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, and is the first talc suit to reach trial in Philadelphia.

Kleiner’s attorney told the jury that the "law is quite clear" that J&J had a responsibility to ensure the safety of talc despite the fact that baby powder is a cosmetic product and not a drug.

According to the U.S. Food & Drug Administration, cosmetics are not FDA-approved, but they are regulated by the agency. FDA regulations on cosmetics state, “Neither the law nor FDA regulations require specific tests to demonstrate the safety of individual products or ingredients. The law also does not require cosmetic companies to share their safety information with FDA.”

Plaintiff’s attorney Leigh O'Dell presented J&J’s internal documents to the jury dating back to the 1940s that include scientific evidence suggesting that the use of talcum powder in the genital area could cause cancer.

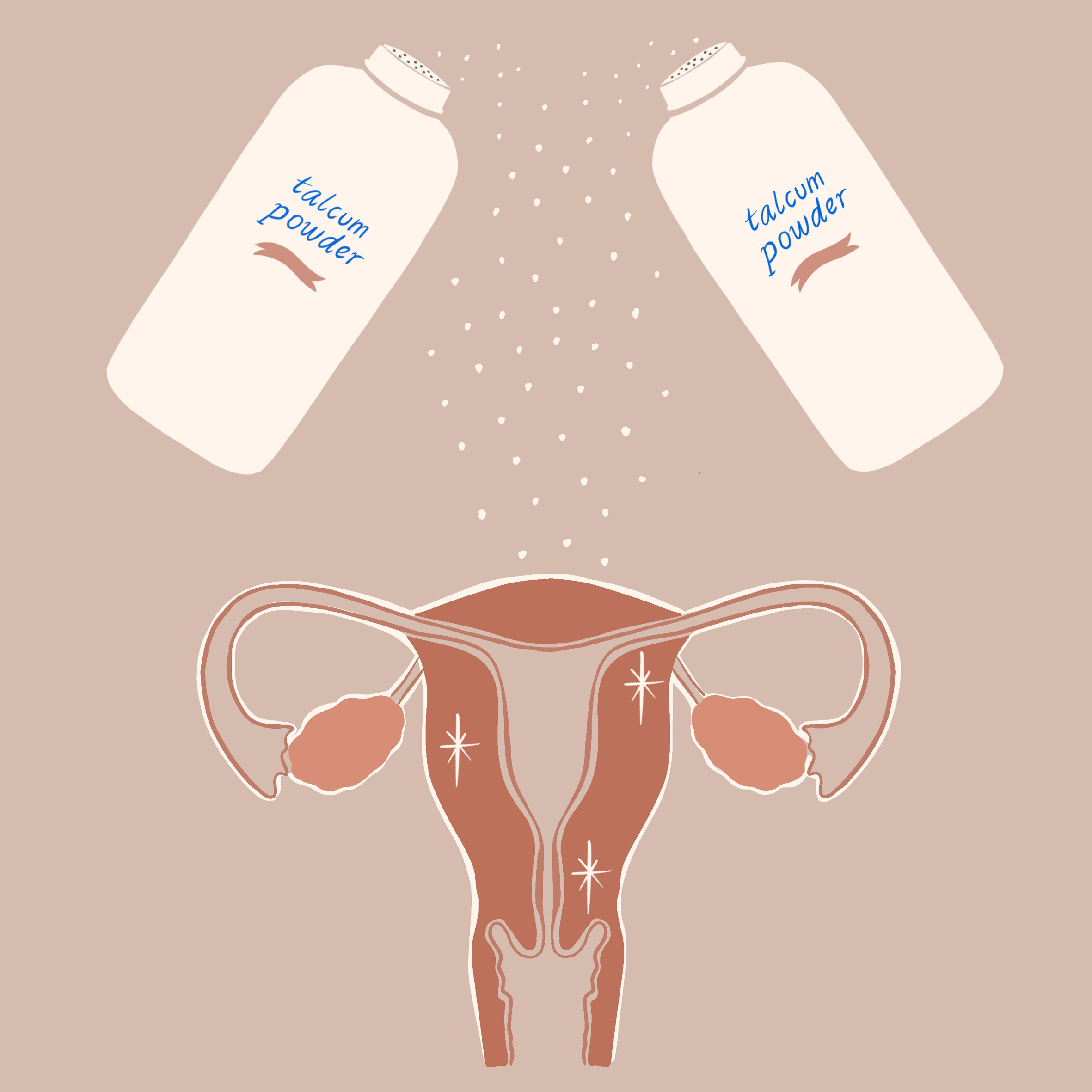

Talcum powder may be contaminated by asbestos, a cancer-causing mineral with no safe levels of exposure yet established for public health, according to the National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety.

William Longo, an asbestos expert witness who has been called to testify in several talc trials, said earlier this year that asbestos in talc is unavoidable.

Attorney O’Dell told the jury that J&J withheld scientific evidence for decades, and that “information was not conveyed to customers because J&J was determined to preserve the iconic brand's image of ‘purity, sanctity and love.’”

Expert witness for Kleiner, Dr. Laura Plunkett, testified that warning labels are required on cosmetic products like talcum powder “when there is even a possibility of a health risk,” Law360 reported.

Kleiner alleged that she used J&J talc baby powder for 34 years and developed cancer because of it.

Studies on the relationship between talc-product usage and cancer are mixed. However, juries that have awarded big payouts to talc powder plaintiffs have found that daily long-term usage of talc was a contributing factor in the development of plaintiffs’ cancer—though not necessarily the only cause of the disease.

The central argument plaintiffs’ attorneys have articulated in talc lawsuits is that J&J should have placed a warning label on its talc-based products.

Kleiner, who has undergone six chemotherapy operations and two surgeries to remove her reproductive organs, allegedly used J&J's talcum powder for 34 years.

Attorneys for J&J stated during opening arguments that a warning label was not necessary, based on evaluations by several government agencies such as the FDA, which in 2014 denied 1994 and 2008 citizen’s petitions to place a cancer warning label on talc products.

“FDA did not find that the data submitted presented conclusive evidence of a causal association between talc use in the perineal area and ovarian cancer,” the FDA’s denial letter read.

For several years, J&J executives maintained that their talc products were safe and free of asbestos. According to Reuters, former J&J CEO Alex Gorsky testified in a deposition in 2019, “We unequivocally believe that our talc and our baby powder does not contain asbestos.”

After the FDA discovered asbestos in a bottle of talcum powder in 2019, J&J voluntarily recalled a batch of 33,000 bottles.

In June, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected J&J’s appeal of a Missouri court’s $2 billion award that went to 20 women who allegedly developed ovarian cancer because of talc powder.